A longstanding goal of American politicians on the left and the right—including and especially the last two U.S. presidents—is to boost not just American manufacturing but American manufacturing jobs. Just yesterday, in fact, President Donald Trump celebrated his first 100 days at a Michigan community college, where he praised his tariffs and claimed to be “taking back our jobs and protecting our great American auto workers.” And almost every time the president or anyone else in his orbit defends current U.S. trade policy in the media, they’ll cite factory jobs—particularly those for high-school educated Americans—as a primary and clearly necessary aim.

The Trump folks certainly aren’t alone. Central to most economic nationalists’ support for blanket tariffs, industrial subsidies, and related government policies is that a dramatic increase in the number of Americans working in manufacturing—a return to days when industrial workers were 20 or even 30 percent of the workforce as opposed to the roughly 8 percent today—would be both feasible and desirable for both the workers and the nation. Implement a giant tariff wall, so these theories go, and you’ll have millions of Americans lined up for shifts at now-busy U.S. factories across the country, and the country will prosper as a result.

In reality, however, there are many reasons to doubt that many millions of Americans—you’d need to add roughly 20 million new factory workers to our current 13 million to get to 20 percent of the US workforce in manufacturing—are itching to work in a factory, that the jobs they filled would necessarily be good ones, or that such an increase would even be possible today, especially via trade policy.

Do Most Americans Really Want to Work in Manufacturing?

The most obvious place to start is with what Americans think about manufacturing jobs. Cato’s 2024 globalization survey explored this very thing and found that while about 80 percent of Americans thought the nation would be better off with more manufacturing jobs, few of those same respondents—around 25 percent—actually wanted to work in a factory themselves. Thus, as my Cato colleague Colin Grabow wrote last year, “Americans love the idea of people working in manufacturing, but most don’t think they would benefit from such work themselves.”

Protectionists nevertheless seized on these data—which recently went viral after being featured in the Financial Times—to argue that there’s a massive pent-up demand for more manufacturing work, since just around 8 percent of the U.S. workforce today is employed in the sector but 25 percent of respondents wanted such work. But these claims fail for two big reasons.

The first is that they simply misread and overstated the poll results. AEI’s Scott Winship dug into the data and found several reasons to question the protectionists’ main conclusion. For example, around the same share of homemakers, students, and permanently disabled respondents expressed a preference for factory work as did full-time workers—a clear indication that said preference isn’t real or, at least, very strong. (Unemployed workers had a stronger preference, but that’s to be expected and we unfortunately didn’t ask about taking a job in another industry.) The full-timers, in fact, had a “strong potential interest” in manufacturing employment just a bit more (1.6 times) than the actual share of said workers currently employed at a factory. Thus, even respondents’ stated preference for manufacturing work in the abstract—i.e., just what they tell pollsters they want in response to a single, vague question—isn’t clear or overwhelming at all.

Even more importantly, however, is Americans’ revealed preference—i.e., what they’re actually doing in today’s U.S. labor market—for manufacturing work. And here there’s little evidence of a strong interest among most American workers, whether employed or sitting at home. As Winship notes, for example, there are almost 500,000 job openings in the U.S. manufacturing sector today, and they’ve actually been getting more common relative to overall manufacturing employment since the Great Recession:

Other data reveal similar disinterest. Reason’s Jack Nicastro, for example, notes that both total U.S. manufacturing employment and the sector’s unemployment rate declined between August 2024 and March 2025, thus indicating that “workers are leaving the manufacturing labor force by choice,” not by necessity. (The unemployment rate in manufacturing today sits at a miniscule 3.1 percent.) And the Census Bureau recently found that more than 20 percent of U.S. manufacturing plants operating below full capacity cited labor or skills shortages as the main reason.

Contrary to White House spin, moreover, there’s not a vast reservoir of unemployed people, especially men, just itching to work in a factory. In terms of sheer numbers, we discussed last year, the common claim that 7 million working-age American men are sitting at home waiting for a job is wildly incorrect. (It’s maybe a fifth of that amount, though exact numbers aren’t available.) The Chamber of Commerce calculates that as of March 2025 there were only eight unemployed American manufacturing workers for every 10 job openings in just durable goods manufacturing.

Various surveys of U.S. manufacturers reinforce these data, with employers routinely citing difficulty finding (and keeping) workers among their top challenges. According to the latest figures from the National Association of Manufacturers, in fact, 67 percent of their members cited “the inability to attract and retain employees as their top primary challenge.” Folks actually recruiting for these positions—even in strategic, unionized, and protected industries like shipbuilding—are constantly complaining about their inability to fill open positions with currently available Americans. And an April 2024 report from Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute found that this problem will only get worse in the years ahead, with “about half of the 3.8 million new manufacturing jobs expected to open up by 2033 likely to go unfilled.”

This situation isn’t entirely about American workers’ revealed preference for (or against) factory work, but surely some of it is. In general, U.S. manufacturing is a sector in need of more workers, not one in need of more jobs.

Are All Manufacturing Jobs ‘Good’ or Needed Jobs?

Some of that revealed preference stems from the fact that many manufacturing jobs today—especially the ones available to workers with just a high-school degree—aren’t what you’d consider “good” jobs in terms of wages, benefits, or job security. And this reality is especially clear when you compare the manufacturing jobs we already have to reasonably available alternatives in the U.S. market, including for “blue collar” men without a college degree.

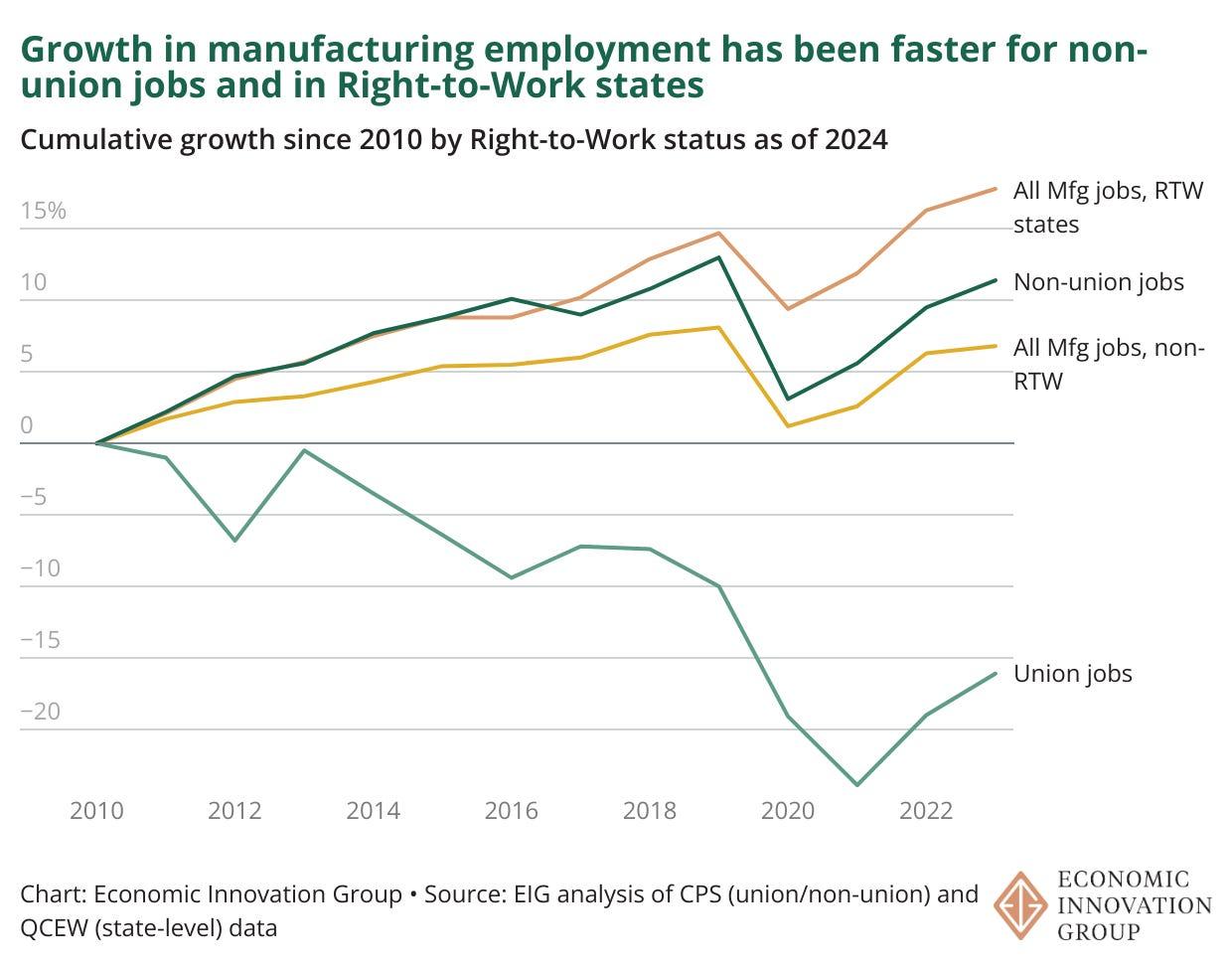

For starters, manufacturing jobs today aren’t necessarily more stable or secure than services jobs. As my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne explained in 2019, for example, the last few decades have seen vast swaths of low-skilled manufacturing work disappear (for reasons discussed next), low levels of new jobs created (despite the aforementioned openings), and net job destruction in the sector overall. Manufacturing jobs are also highly sensitive to recessions, with big, deep cuts during the last several downturns. As a recent Economic Innovation Group analysis demonstrated, moreover, most of the manufacturing jobs created in the United States today aren’t unionized, as the recent uptick has been mostly in the high-growth, lower-cost, right-to-work South:

Then there are wages, where American manufacturing jobs’ premium over services jobs disappeared years ago. In 2023 and 2024, in fact, hourly earnings for blue collar (aka “production and nonsupervisory”) workers in manufacturing paid significantly less on average than the same workers got paid in the services sector:

My Cato colleagues Norbert Michel and Jerome Famularo add that this differential isn’t just about white collar services industries (doctors, bankers, tech bros, etc.), either: “As of September 2019, average hourly earnings for nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing were lower than average earnings in 7 out of 10 service-sector categories created by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.” And, they note, these figures are probably too kind to manufacturing: Wages there “tend to be inflated relative to those in service industries because the manufacturing sector’s workforce is older.” Because younger workers typically get paid less, services’ “larger share of young workers clearly places downward pressure on average income for service jobs at the industry level.” Put another way, U.S. services wages would probably compare even better to U.S. manufacturing wages if you considered workers of the same age.

Drilling into specific industries—especially the ones most affected by globalization—shows similar manufacturing wage weakness. As we discussed in December, for example, the few remaining textile and apparel jobs in the United States are—even with already-high U.S. trade barriers—relatively low-paying, and companies thus struggle to find workers today. The Seattle Times reports, in fact, that the median hourly wage for U.S. sewing machine operators in “cut and sew apparel manufacturing” was just a little more than $16—around 40 percent below the median U.S. wage. Even wages at luxury brands selling expensive stuff aren’t great: Jobs at fancy local clothing manufacturer Filson start at $21/hour, but that’s just a few cents above the local minimum wage. Given the pay and the nature of the work itself, the company and others like it can’t find workers nearby (emphasis mine):

Many garment workers in immigrant communities are aging out and aren’t passing those skills on to their children… Many “worked really hard to send their kids to school so that they wouldn’t have to … work in the factories anymore,” Zwiers said. In the Seattle area, skilled apparel labor has become so scarce that when Outdoor Research wanted to expand production, around six years ago, the company had to look elsewhere and eventually settled on the Los Angeles area, which still has a lot of apparel workers, Zwiers said.[block]

Similar issues abound outside of Seattle and in other manufacturing industries. As we found in Georgia, for example, the 2024 median hourly wage in apparel manufacturing and textile manufacturing paid just $15.49 and $17.56, respectively. In South Carolina, meanwhile, a garment worker will start at just $11 an hour, and locals in a former textile town are “baffled” as to why anyone would want to bring back the unsafe, low-paying mill jobs that left their community decades ago. And protectionists who cheer Trump’s washing machine tariffs conveniently ignore that production line jobs at Samsung’s new(ish) U.S. plant start at just $16-$17 an hour and “require standing for long hours, with short breaks, and the ability to lift up to 35 pounds.” (Each job also cost U.S. consumers a staggering $800,000 per year, thanks to those tariffs.) As I wrote in 2021, several other manufacturing industries also pay relatively low wages compared to most services.

Of course, not all U.S. manufacturing jobs are low-paying and exhausting, but even American manufacturers with wages higher than many services (and ones enjoying import protection) still find hiring difficult. In 2019, for example, Bloomberg reported that furniture makers in North Carolina were offering signing bonuses and up to $35 an hour—mainly for making pricey, custom-order pieces—but still couldn’t find young people eager to do the physically demanding work. “Just getting good applicants is a problem,” said one furniture company’s HR director. Steel jobs in Arkansas, Reuters reported last week, pay $100,000 a year or more, yet steel companies there and elsewhere still have many unfilled jobs, due to both the skills required and the “largely accurate” perception among workers that “even manufacturers who invest in sparkling new operations will readily shut or curtail them when the economy turns sour.”

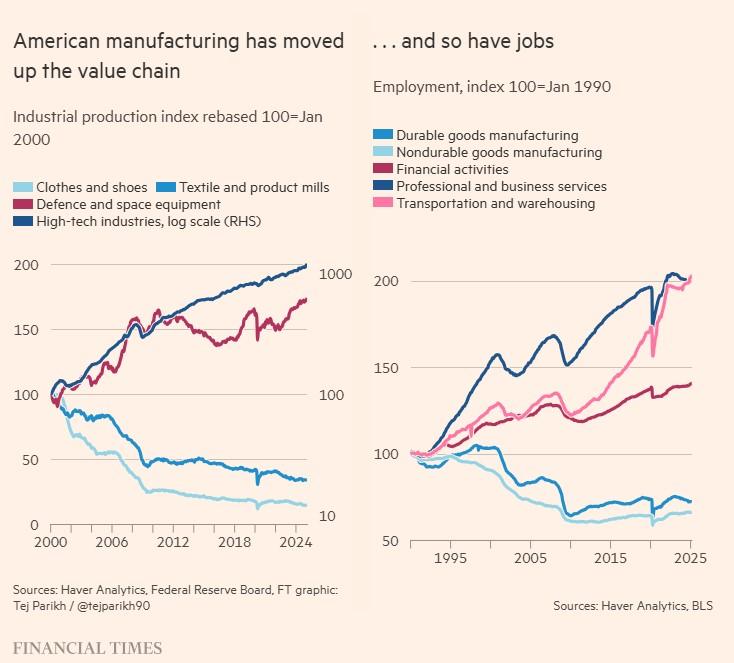

Furthermore, many of the “good jobs” in manufacturing don’t comport with the nationalist narrative. First, as we discussed last January, a lot of the better-paying work in the sector today is in services or requires advanced skills and post-secondary education—far different from the routine assembly line jobs of the past that required only a high school degree. As the FT’s Tej Parkih just documented, moreover, one reason we have these jobs today—and why American incomes and advanced manufacturing jobs have grown since the 1990s—is good ol’ globalization. In particular, we outsourced the lower wage, routine work protectionists want to bring back, and shifted American workers and other resources into higher value economic activities, such as services, research and development, and advanced manufacturing:

And herein lies the rub: High-enough tariffs might be able to reshore labor intensive industries like textiles (at a massive cost, of course), but—because there’s no vast surplus of available, eager labor—doing so would inevitably come from shifting finite resources away from the higher-value activities in which our workforce specializes today. Put another way, we’ll be gaining mediocre jobs nobody really wants at the expense of better jobs they actually do.

The availability of alternative jobs outside of manufacturing looms large in this discussion. As I first noted in my 2023 book, for example, there are around four times as many jobs in blue collar, male-dominated industries than in manufacturing:

These and other “manly” jobs often pay as well or better than durable goods manufacturing, and they’re often more attractive:

Even low-skill services jobs can pay well today. Average associate wages at Walmart and Amazon are more than $18 an hour and $22 an hour, respectively; are coupled with decent benefits; and can eventually go much (much!) higher. Most Costco workers today make $30 per hour, plus benefits. Economist Jeremy Horpedahl gives an even starker comparison:

In short, sure some manufacturing jobs today are “good jobs,” but these typically require more education, still struggle to attract American workers, still face stiff competition from many comparable services, and—given how much modern manufacturing and modern manufacturing jobs depend on trade—probably wouldn’t be helped by blanket tariffs, anyway. None of this means we should cheer when Americans lose their jobs or favor policies that actively discriminate against manufacturing employment, but it does argue strongly against brute-force efforts to blindly expand the manufacturing workforce without regard to the actual jobs getting created—or their economic cost.

Can Tariffs Really Bring These Jobs Back?

Finally, there’s the important question of whether trade policy (or any policy, tbh) really can return us to mid-20th century levels of manufacturing work, even if the jobs were great and there were an eager and willing supply of American workers to fill them. And here, again, there are reasons to doubt the nationalist spin.

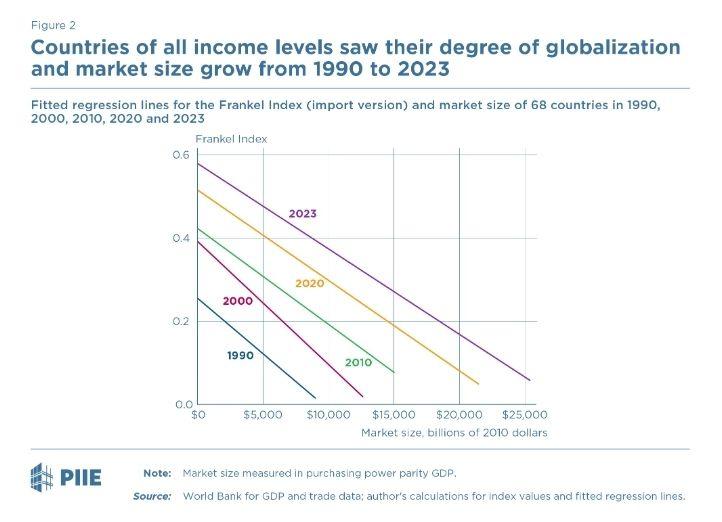

For starters, declining manufacturing jobs aren’t a U.S.-specific phenomenon or something driven mainly by international trade. Instead, as The Economist detailed last week, “disappearing factory jobs are an inevitable part of economic development.” As countries start to get richer and industrialize, more of their citizens move into manufacturing. After a certain level of wealth, however, “employment shifts once again from industry to services and manufacturing jobs decline.” The result is the inverted “U” pattern of development that happens basically everywhere in the world:

As I explained in my 2021 paper, other analyses confirm this same trend, as does this new review from international economist Kyle Handley (and this new one too). This unavoidable “economic gravity” helps to explain why manufacturing jobs in the United States started steadily declining long before the “hyperglobalization” period of the 1990s and why they’ve been declining in places with higher tariffs or longstanding trade surpluses:

And it explains, as Handley notes, why the same trend is happening in China today too:

As the Financial Times noted in March, in fact, China has lost more than 7 million manufacturing jobs since 2011, in many of the same industries that saw such attrition in the United States decades ago:

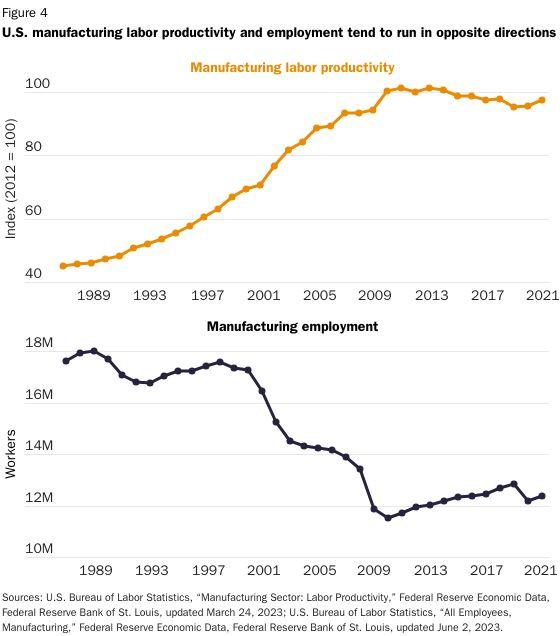

As that piece noted (and as I explained in 2021), trade certainly played a role in manufacturing’s declining share of nations’ workforces, but other, nontrade forces are the main drivers. First, as Harvard’s Robert Z. Lawrence details in his new book, there’s productivity (making more stuff with fewer people) and recessions:

For overall manufacturing, the story is simple: Lawrence finds that rapidly increasing productivity explains all job loss in the US. For the non-computer sector…, the picture is a little more complicated. From 2000 to 2010, half the employment losses are still due to productivity growth, but slow economic growth, caused largely by two recessions, explains much of the rest. He provides two estimates: in one, trade explains a little under a quarter of the job loss in non-computer manufacturing, and in the other, it explains none. Either way, it’s not the main part of the story.

Productivity gains mean both that trade wasn’t the biggest cause of past manufacturing job losses, and that you’d need a huge and unrealistic increase in current U.S. industrial output to achieve the same number of jobs we used to have in the sector.

The other big, nontrade driver is, as The Economist explains, changing consumption patterns as we get richer:

When incomes rise in poor countries, individuals tend to spend less on food and more on manufactured goods, a phenomenon known as Engel’s law. When incomes rise in rich countries, consumption shifts away from manufactured goods towards services. In 1950 goods accounted for around 60% of American consumption; today they represent just a third of spending with services accounting for two-thirds.

Put another way, once Americans—or anyone else—reach a certain level of wealth and have accumulated a certain amount of physical stuff (especially big ticket durable goods like cars and appliances), they devote most of their remaining earnings to services. As those remaining earnings keep growing, a nation’s services sector grows to satisfy that demand. So, even with a healthy manufacturing sector and increasing output, the sector’s share of the economy can shrink—something that’s happened in the United States and many other nations around the world (including, again, places with lots of exports and trade surpluses). Jobs inevitably follow suit.

Add in the not-insignificant fact that much of the world was either bombed-out or embracing self-destructive communism when manufacturing jobs peaked in the United States, and it becomes clear that attempting to use trade policy to broadly “reindustrialize” the American workforce back to levels last seen in the 1950s or 1960s is nothing short of impossible. And, given the availability of good-paying alternative jobs and the high costs that any such initiative would entail, it’d be delusional (at best) to pursue it.

Summing It All Up

Political promises to “bring back” millions of U.S. manufacturing jobs ignore several inconvenient yet essential facts. First, neither Americans’ stated nor revealed preferences indicate that several million Americans are just itching to make T-shirts or smartphones or toasters. Second, many U.S. manufacturing jobs today—and many of the jobs that might be encouraged via tariffs—are neither good-paying nor in high demand, and forcing them back into the country would inevitably mean fewer of the good jobs we now have. Finally, even if Americans really did want these subpar factory jobs, resuscitating even a fraction of the number needed to achieve the American workforce of the mid-20th century would require defying an economic gravity affecting basically every nation on the planet, including China.

And all this ignores—as too many of these newsletters have detailed—other flaws in the nationalist narrative, such as the fact that the U.S. manufacturing sector is large and competitive, or that subsidies and protectionism are hardly good and effective way to improve it, or that economists generally consider jobs a cost of production, not a benefit. Yet you could grant those mistaken premises and still easily conclude that promises to use blanket tariffs to reengineer an industrial workforce of our parents’ distant memories are laughably out of touch.

No wonder they’re a hit on the campaign trail.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.